An age-old mystery of fitness — when and how much does one eat after a training session? Are all the potential gains lost if the body is not refueled within a particular window of time post-workout? Will the efforts in the gym be squandered by a lack of macro-friendly, protein-packed food at the ready? The short answer is no, but there is some nuance to those questions that deserve proper context, as well as some baselines you can adjust your schedule with to help maximize the dividends of your training effort.

Let’s dive into what the science says about when and how much to eat after pressing barbells and spamming burpees, what caloric range for post-workout meals is appropriate, and why macro-balanced meal replacements like Ample Recover: Performance Meal Shake could be a valuable resource on the go.

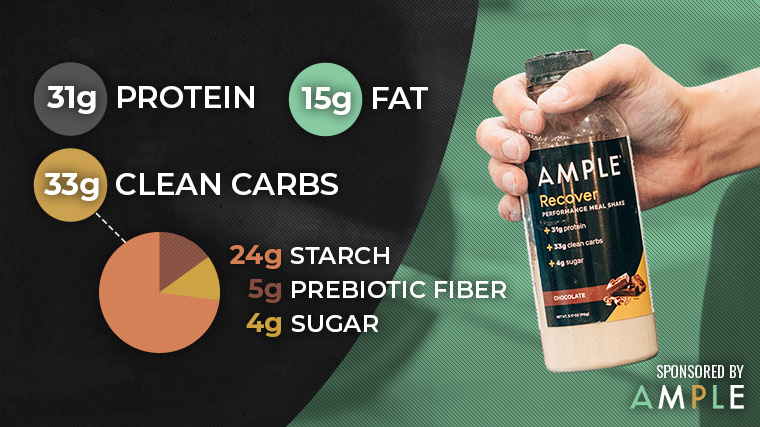

This meal shake packs 400 calories with a macro breakdown of 15 grams of fat, 33 grams of carbohydrates, and 31 grams of fat. Each 90-gram bottle comes in a chocolate flavor.

How Many Calories Post-Workout?

First, the optimal caloric intake post-workout isn’t one size fits all. The caloric needs will change with each individual and the intensity of the workout. That said, there are baselines for carbohydrate and protein intake to help optimize muscle protein synthesis after training. It’s important to note that eating before a workout, regardless of how long before training, can positively impact glycemia — the presence of glucose in the blood — when eating a post-workout meal. (1) So why is it important to eat after training?

Restoring glycogen levels post-workout is an essential part of recovery. Neglecting to do so could result in suboptimal recovery and prolonged fatigue due to training. For reference, glucose is sugar in the bloodstream used for energy. Glycogen is glucose that has been stored in the liver, brain, and skeletal muscles. Glycogen in the skeletal muscles is used “during high-intensity exertion,” according to Annals of Translational Medicine. (2)(3)

If eating after training fuels proper recovery, that begs the question: how much should you eat after your workouts? Evidence suggests that with age comes a need for more protein post-workout. Twenty grams of protein has been found sufficient for young, healthy individuals and adults to promote desirable muscle protein synthesis. However, older individuals (mid-60s and over) saw similar results with 40 grams of protein post-workout. Frontiers in Nutrition found that 0.31 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, regardless of gender, is “a suitable target to maximize myofibrillar protein synthesis.” (4)(5)(6)

While it is favorable to eat whole foods if possible after a workout, meal shakes like Ample Recover can be an “effective strategy for physically active adults to meet protein recommendations.” (7)

When Should You Eat Post-Workout

In the event of training fasted, eating a combination of protein and carbohydrates immediately after training can facilitate muscle protein synthesis to push your metabolism towards an anabolic state rather than a catabolic one. For those with the goal of muscle hypertrophy, the optimal window to consume a meal is within two hours after the training session. (2)

However, consuming a combination of carbohydrates (0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight) and protein (0.2-0.4 grams per kilogram) within a four-hour window post-workout can “support increases in strength and improvements in body composition,” per the position stand of the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. (8)

How to Find Your Macros

The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institutes of Medicine recommends the following broad scope for energy intake (i.e., daily calories):

- Carbohydrates: 45-65 percent of your daily caloric intake

- Protein: 10-35 percent of your daily caloric intake

- Fat: 20-35 percent of your daily caloric intake (limit saturated and trans fats)

For more active individuals, more specific carbohydrate and protein recommendations are five to 12 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight and 1.2 to 1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, depending on the level of physical activity. (9) There are a lot of factors to take into account when it comes to deciphering physical activity and balancing total calories, so here is a macronutrient calculator to make it easier to find a starting point:

Macronutrient Calculator

Just over 30 percent of Ample Recover: Performance Meal Shake’s 400 calories are from protein — 31 of 90 grams. It delivers slightly more carbohydrates — 33 grams — making it a potent combination of protein and carbohydrates in a quick three-ounce drink that is easy to take on the go. Meal replacements for those with busy schedules have been shown to improve metabolic parameters and even support improvements to body composition for individuals with active lifestyles. (10)

So next time you squeeze in a training session and don’t have time to grab a meal consisting of whole foods, reach for an Ample Recover: Performance Meal Shake, replenish your body with the protein and carbohydrates it needs to refuel. Hopefully, your recovery, and therefore your training, will improve as a result.

This meal shake packs 400 calories with a macro breakdown of 15 grams of fat, 33 grams of carbohydrates, and 31 grams of fat. Each 90-gram bottle comes in a chocolate flavor.

References

- Aqeel, M., Forster, A., Richards, E., Hennessy, E., McGowan, B., & Bhadra, A. et al. (2020). The Effect of Timing of Exercise and Eating on Postprandial Response in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 12(1), 221. doi: 10.3390/nu12010221

- Aragon, A., & Schoenfeld, B. (2013). Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window?. Journal Of The International Society Of Sports Nutrition, 10(1). doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-10-5

- Kanungo, S., Wells, K., Tribett, T., & El-Gharbawy, A. (2018). Glycogen metabolism and glycogen storage disorders. Annals Of Translational Medicine, 6(24), 474-474. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.59

- Moore, D., Robinson, M., Fry, J., Tang, J., Glover, E., & Wilkinson, S. et al. (2008). Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. The American Journal Of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), 161-168. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26401

- Yang, Y., Breen, L., Burd, N., Hector, A., Churchward-Venne, T., & Josse, A. et al. (2012). Resistance exercise enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis with graded intakes of whey protein in older men. British Journal Of Nutrition, 108(10), 1780-1788. doi: 10.1017/s0007114511007422

- Moore, D. (2019). Maximizing Post-exercise Anabolism: The Case for Relative Protein Intakes. Frontiers In Nutrition, 6. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00147

- van Vliet, S., Beals, J., Martinez, I., Skinner, S., & Burd, N. (2018). Achieving Optimal Post-Exercise Muscle Protein Remodeling in Physically Active Adults through Whole Food Consumption. Nutrients, 10(2), 224. doi: 10.3390/nu10020224

- Kerksick, C., Arent, S., Schoenfeld, B., Stout, J., Campbell, B., & Wilborn, C. et al. (2017). International society of sports nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. Journal Of The International Society Of Sports Nutrition, 14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12970-017-0189-4

- Manore, M. (2005). Exercise and the Institute of Medicine Recommendations for Nutrition. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 4(4), 193-198. doi: 10.1097/01.csmr.0000306206.72186.00

- Guo, X., Xu, Y., He, H., Cai, H., Zhang, J., & Li, Y. et al. (2018). Effects of a Meal Replacement on Body Composition and Metabolic Parameters among Subjects with Overweight or Obesity. Journal Of Obesity, 2018, 1-10. doi: 10.1155/2018/2837367

Featured Image: Mix Tape/Shutterstock